Dependency What?

Welcome to the Dependency What? workshop. My name is Thomas Presthus, and I’ve been working as a consultant doing software development and architecture for the past ten years.

This workshop premieres at the NNUG Vestfold Kodekafé. That means that you, dear participant, is one of the first people to ever take part in it. Since this is the premiere, I ask of you to please raise any questions or problems you may encounter on your path here tonight. I further hope that we won’t exceed our time slot. Furthermore I’d like to thank Verftet for hosting us - please take the opportunity to order yourself a coffee or beer to show our gratitude.

Now for the fun part! What is this workshop all about? I’d say it’s mainly about the Dependency Inversion Principle, but with bits thrown in about Inversion of Control, containers (not the docker/LXC ones!) and Dependency Injection as well. (Big words, I know!)

I’ve found throughout the past years that while many developers kinda understands the principles behind these words, many also struggle to explain the difference between them and perhaps also to implement them in actual code.

That’s why we’ll try to break down the principles and approaches to implementing them, and hopefully giving a little more insight to how they help us and our codebases.

Prerequisities

Since this workshop is hosted by NNUG Vestfold, we’ll use C# as our language of choice in code samples and excercises. The principles and patterns we present should, however, apply to most object-oriented languages. Most of them applies to functional languages as well, but those tend to have other mechanisms that might be more idiomatic (see e.g. my blog post on Scala and the Cake Pattern).

You should have a functioning development environment of your choice (e.g. Visual Studio or perhaps vim and mono?). You should also have a basic understanding of object orientation.

Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP): 101

What is the Dependency Inversion Principle (hereafter known as DIP)?

The principle itself was probably first described by Robert “Uncle Bob” Martin along with the SOLID principles.

It states:

A. High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions.

B. Abstractions should not depend on details. Details should depend on abstractions.

Simple enough, right? Read it again and try to dig into its actual meaning. Abstractions should not depend on details. What are these details and abstractions?

In object orientation we create abstractions and concrete implementations in order to modularize and reason about our systems. It’s not always easy to come up with helpful implementations though. Consider the following example:

interface IClient

{

string FirstName { get; set; }

string LastName { get; set; }

IList<Address> Addresses { get; set; }

void Activate();

void Deactivate(string reason);

void AddAccount(IAccount account);

void Deposit(double amount);

}Interfaces in C# are one kind of abstractions. They define an interface that other types can implement, and thus signal their supported operations to their consumers.

Is the above code a good abstraction though? While, yes, it’s an interface and not a concrete implementation, it seems to offer no abstraction. It’s rather a means of indirection.

So what would we consider a good abstraction? We would have to abstract something away, right? Let me give you an example.

My car has automatic transmission, meaning that I don’t have to manually shift gears. When I think of automatic transmission, this is what I envision:

Picture by Brian Hoecht under Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND

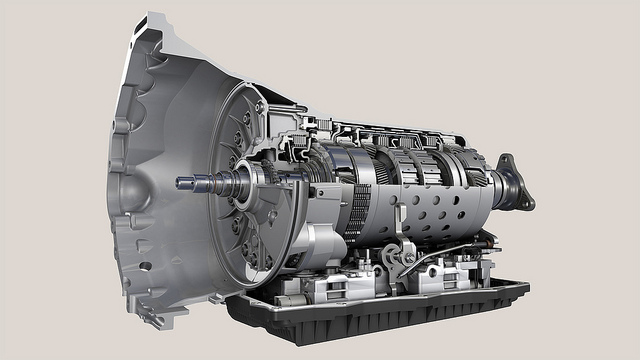

This is however what an automatic transmission actually looks like:

Picture by Abdullah AlBargan under Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0

See how the first image, the shifter, abstracts away how the automatic transmission works? Imagine the interface describing the actual transmission!

Excercise

Try to define an interface for the automatic transmission shifter in your language of choice.

You could end up with something like this when you’re done.

That’s probably pretty easy. Don’t worry though, we’ll get to more complex abstractions in a little while.

What does this abstraction give us? First of all, it’s an interface that would seem natural and comprehendible by any driver. Like the driver, the abstraction would make sense to a coder trying to use your interface - allowing him not to worry about how the underlying machinery actually works.

By now you might be wondering what automatic transmissions has to do with the DIP. There are no dependencies in the code yet. Let’s revisit the principle briefly: Code should depend on things that are at the same or higher level of abstractions.

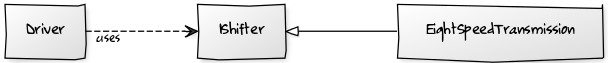

We can draw this:

Notice that the IShifter abstraction has do depencies while the EightSpeedTransmission, by implementing it, has a dependency on IShifter.

Let’s extend our system by adding a Driver:

Notice how we now introduce another detail, Driver. The Driver has a dependency on IShifter. This adheres to the DIP since we have no abstractions depending on details. Both details are depending on an abstraction.

We could, of course, have made our Driver depend directly on the EightSpeedTransmission instead, but this would violate the DIP.

Excercise

Implement the above type system in your favorite language

That about wraps up the introductory chapter on Dependency Inversion Principle. This far we’ve learned that it’s in fact a very simple principle that helps us create modularized and loosely coupled code by not having details depend on details.

Inversion of Control

We’ve talked about the inversion of dependencies. Now we’re going to have a look at the inversion of control (whatever that means, right?).

I personally think the main reason that developers struggle with DIP, DI, IoC and containers is that the naming of these concepts are so similar. I mean; Dependency Inversion, Inversion of Control, Dependency Injection. It all seems to overlap. I’ve talked to developers who thinks Dependency Inversion requires Inversion of Control Containers, or that Dependency Inversion and Dependency Injection are the same things. And aren’t Inversion of Control the same as containers?

We’ll come back to the container later, and focus on Inversion of Control as a principle.

When writing code, we traditionally let the consumer of a component call it - thus being in control. This isn’t necessarily a Bad Thing™, but it’s all about how we do it.

Consider the following example:

class Autopilot

{

// Attempt to overtake the next car

// by signalling a turn, shifting to a lower gear

// and turning left (hoping that we're not in Britain)

public async void Overtake()

{

var blinker = new BlinkerService();

using(blinker.SignalLeft())

{

var shifter = new ShifterService(new EightSpeedTransmission());

await shifter.GearDown();

var steering = new SteeringService(new ServoBasedSteering());

await steering.TurnLeft();

}

}

}While the code is simple, it hides three major dependencies:

- Shifter

- Blinker

- Steering

This makes it hard to compose this component together with the rest of our car, since as a caller we have no idea of which dependencies will be used. It also makes it harder to test.

Another problem with the code is that the Autopilot is now made responsible for both creating and maintaining the life-cycle of these depencies. We could call this classical Control (with no inversion).

Utilising Inversion of Control, we’ll invert the control chain, releiving the Autopilot from the responsibility of maintaing the life-cycle for these dependencies.

There are several ways we can do this. For now, we’ll use the Service Locator pattern. Please note that this is considered an anti-pattern - we will explore better alternatives a little later.

Instead of re-iterating the mechanics of the Service Locator, I’ll leave it as an excercise for you to read about it here.

Excercise

Try refactoring the above code into using a Service Locator. You can mock out the Service Locator implementation to make it easier for yourself.

You could end up with something like this.

To use the Autopilot, we can now do this:

void Main()

{

ShifterService.Current = new ShifterService(new EightSpeedTransmission());

SteeringService.Current = new SteeringService(new ServoBasedSteering());

BlinkerService.Current = new BlinkerService();

var autopilot = new Autopilot();

autopilot.Overtake().ConfigureAwait(false);

}Notice how the Autopilot no longer knows anything about transmission systems or how the steering works. It simply uses the dependencies that are controlled by the main loop. We have successfully inverted the control of our dependencies.

Furthermore we’ve adhered to the Dependency Inversion Principle of not having details depend on other details. The Autopilot detail depends on three abstractions: ShifterService, SteeringService and BlinkerService. ShifterService uses an IShifter (remember?) which we construct as an EightSpeedTransmission detail in our composition root. The same goes for the SteeringService.

Wait. Did I just say composition root? What’s that? Read on to find out (or google it).

Dependency Injection

Did you think we were finished with dependencies yet? Nope. This is where we shake it up by adding to the confusion of acronyms. We’lve talked about DIP, and now we’re gonna look at DI: Dependency Injection. Finally a term without Inversion in it!

As we’ve already seen, Dependency Inversion is about separating implementation details and abstractions. Inversion of Control is about inverting the control and life-cycle management of dependencies. So what is Dependency Injection?

Simply put, Dependency Injection is a pattern and a means to achieving Inversion of Control. In the previous chapter, we implemented IoC by using the Service Locator pattern. This is, however, considered an anti-pattern since it hides the dependencies of a component.

Imagine that someone else wanted to use the Autopilot we created. They’d probably start with:

void Drive()

{

var autopilot = new Autopilot();

autopilot.Overtake();

}It would compile nicely, but when they run their method it would crash and burn. Why? Because they didn’t initialize the required dependencies in the Service Locator. In order to get it running, they would have to open the source of the Autopilot class and walk through every single line to find its dependencies.

This should not be necessary. Instead we should strive to both let the Autopilot signal to its consumers what it needs to work, and also have the compiler not accept code that won’t run.

Dependency Injection is all about injecting our dependencies into the component that needs them. In object-oriented languages we have primarily two approaches to implementing Dependency Injection: Constructor-based injection and setter-based injection.

Setter-based injection

In C# this is also known as property-based injection. Consider the following example:

class Component

{

public FooDependency FooDependency { get; set; }

public BarDependency BarDependency { get; set; }

public void DoSomething()

{

var fooValue = FooDependency.CalculateValue();

BarDependency.Send(fooValue);

}

}Instead of having our code call out to a common service locator, we now state that we have two dependencies (FooDependency and BarDependency) that should be initialized from the outside like this:

void Main()

{

var foo = new FooDependency();

var bar = new BarDependency();

var component = new Component

{

FooDependency = foo,

BarDependency = bar

};

component.DoSomething();

}By doing this, we inject the dependencies into our component instead of having the component reach out to a global service locator. We also adhere to the DIP. When we’re writing tests for our component it’s also easier to inject the dependencies instead of setting up a service locator.

Excercise

Try refactoring the Autopilot class to use setter-based dependency injection instead of a Service Locator

It doesn’t really feel well, though. Our compiler will still accept the code if we were to construct a new Component without setting the dependency properties, which leads us back to the developer having to open the source code and locating the dependencies.

Constructor-based injection

We want to make the dependencies of our Component explicit, and have the compiler reject our code if we don’t inject the required dependencies. This can be achieved with constructor-based injection.

Instead of declaring our dependencies as properties, we will now add a constructor and declare our dependencies to the component:

class Component

{

private readonly FooDependency _fooDependency;

private readonly BarDependency _barDependency;

public Component(FooDependency foo, BarDependency bar)

{

_fooDependency = foo;

_barDependency = bar;

}

public void DoSomething()

{

var fooValue = _fooDependency.CalculateValue();

_barDependency.Send(fooValue);

}

}If we naively now try to use this component:

void Main()

{

var component = new Component();

component.DoSomething();

}The compiler will reject our code, since we don’t fulfill the requirements of the Component’s constructor. Thank to Intellisense, and its likes, we probably know this before trying to compile. So we alter our code to this:

void Main()

{

var foo = new FooDependency();

var bar = new BarDependency();

var component = new Component(foo, bar);

component.DoSomething();

}It compiles and works. So by using constructor-based injection we get more safety by instructing the compiler to reject our code when dependency requirements are not met, but we also make the code less ambiguous and easier to use.

Excercise

Refactor our Autopilot class from using setter-based injection to using constructor-based injection.

This far we’ve seen how we can invert the control of dependencies through the Service Locator and Dependency Injection patterns. As you can see, Dependency Injection makes our code less tangled and easier to reason about. We’ve also implicity seen how dependencies are controlled in what I called a composition root.

Composition root

So what is this composition root that I talk about? While it’s totally unrelated to the DIP, it becomes quite important when utilising Inversion of Control.

The composition root is basicly where you wire up your application. It’s where we control the creation and life-cycle of our dependencies and components.

In the examples above we’ve used the Main() method to wire everything up, and this is not a coincedence. When creating applications, the main loop is usually the entry point to our application, and thus the point of our stack that has access to all the dependencies. It’s also a natural place to compose our application.

When using some frameworks, however, we don’t have access to the main loop in the same way. This can be frameworks like WPF, ASP.NET, etc.

Those frameworks usually offer other means to wiring up the system, though, and it’s become increasingly popular to embrace this using an IoC container.

Inversion of Control containers

I personally think that IoC containers have participated, at least somewhat, to the confusion regarding DIP, DI and IoC. They have been forced down our throats by frameworks, and they’ve been marketed as “must-haves”.

We will, however, take an introductory look at containers and how they can be leveraged, before touching upon how not to use them.

Looking back at the code we wrote when experimenting with Dependency Injection, we can easily imagine our composition root growing big and hairy. Most of the code residing in the composition root will probably concentrate on constructing components and managing their life-cycles too. Sounds repetitive and error-prone.

This is one of the reasons that IoC containers started to appear. Here are some well-known containers in the .NET world:

- StructureMap

- Spring.NET Application Context

- Castle Windsor

- Autofac

- TinyIoC

- Unity

And these are not the only ones. They all have some differing semantics and mechanisms, but they all try to solve the same problem: Making it easier to adhere to IoC and resolve dependencies.

Go ahead and follow some of the links and read a little about a couple of the containers I mentioned. I recommend reading about StructureMap (the first open-source container for .NET) and Unity (which comes from the Microsoft Patterns and Practices team and is widely used in Microsoft products).

I’ll choose to use StructureMap to demonstrate some of the common features of containers. We’ll start by using explicit registrations and build up our Component and its Foo- and BarDependencies.

Before that, though, we’ll install StructureMap through NuGet:

PM> Install-Package structuremap

void Main()

{

var container = new Container(_ =>

{

_.For<IFooDependency>().Use<FooDependency>();

_.For<IBarDependency>().Use<BarDependency>();

});

var component = container.GetInstance<Component>();

component.DoSomething();

}This doesn’t really look like any less code. Notice that we no longer construct the Component ourself, but rather delegate to the container to resolve it for us.

To be honest, the small example doesn’t really do the container justice. Imagine that we had several components and more than two dependencies, perhaps a complete graph of dependencies. That’s where containers come in handy.

Excercise

Replace the manual wiring of Autopilot and its dependencies with a container, using explicit registration of components

Container can help us write less too. Some of them offer quite sophisticated mechanisms for scanning and automatically registering components. Let’s see how we can do it with StructureMap:

void Main()

{

var container = new Container(_ =>

{

_Scan(x =>

{

x.TheCallingAssembly();

x.WithDefaultConventions();

});

});

var component = container.GetInstance<Component>();

component.DoSomething();

}At this point we’re no longer telling StructureMap which components to be used. We’re only telling it to scan the calling assembly for all types, and when resolving Component it will inspect the constructor to see that it needs an IFooDependency and an IBarDependency. It will then look at all its registered types and find the ones that match our constructor.

With such few dependencies the amount of code is about the same, but it’s easy to imagine how much code we can omit when having just a few more components.

Another benefit is that we can easier refactor the constructors of our dependencies, since the container will resolve them through introspection.

Excercise

Refactor our container based Autopilot main loop to automatically scan for components instead of registering them manually

Here be dragons

I know that containers are starting to look really nice by now. All that code we won’t have to write! A word of advice: Be careful. Containers are really good at resolving complex graphs of dependencies, but they come with the cost of added complexity in the form of indirection and magic. When we have multiple implementations of our abstractions, different conventions and perhaps even XML-based configuration of the container, it becomes increasingly hard to find out how dependencies will actually be resolved.

If you find that a container will ease your job, or that you’ll have to use one because of a framework, please confine the container to your composition root. Do not (and I repeat; do not) pass the container instance along down your graph of dependency. Doing so will actually degrade the container to a glorified Service Locator (which, as we remember, is an anti-pattern).

Wrapping up

First of all; thank you for following me this far. I hope you’ve had fun and maybe learned something new. I’ll try to summarize quickly what we’ve learned today.

Dependency Inversion Principle, Dependency Injection, Inversion of Control and IoC containers are different things, some of them even orthogonal.

Dependency Inversion Principle

Abstractions should not depend on details. Details should not depend on other details.

This keeps our dependency graph untangled and tidy. It also gives us looser coupling and better separation between abstractions and details while helping us to discover actual and good abstractions.

Inversion of Control

Dependency management is done by the code that calls you, instead of you.

By inverting the call chain we gain more structure and top-down control of our components instead of hiding dependencies and tangling code.

Dependency Injection

Dependency Injection is simply a pattern and tactical approach to achieving Inversion of Control by injecting dependencies into components that need them.

IoC containers

Simple containers that can help us manage the creation and life-cycle management of dependencies. They make it easier to resolve complex dependency graphs.

Thank you

I appreciate any feedback or comments you may have – be it criticism, problems, input or anything else. Please reach out to me on Twitter @presthus or by email.

Thank you to NNUG Vestfold for hosting this meetup and workshop.